- Home

- Chelsea Handler

Life Will Be the Death of Me Page 7

Life Will Be the Death of Me Read online

Page 7

I went down to the rescue in Westwood and picked up our new dog. The girls working there told me he could be anywhere between four and twelve. I brought our new family member home and decided his name would be John. He was sweet and goofy and was definitely a big puppy—I figured he was probably two.

That night, in an effort to not overthink assimilating my new brood, I put all three dogs in my bedroom, and popped an edible. I was awakened by a low rumble that rose to a roar, and then to something that sounded like there was a werewolf nearby. When I flipped the lights on, Tammy’s midsize, corpulent body had somehow wrapped itself around John’s, like a contortionist. Thank God for instinct, because I’m scared to think what I would have done had I given it any thought. I screamed “No!” and then ripped Tammy off him. Her eyes were red and she looked like she was wearing red lipstick. I tossed her toward my closet. John was a bigger dog and stronger than I thought, and I couldn’t hold him back from barreling toward her, so I dove right into the middle of them, grabbed Tammy, pushed her headfirst into my closet, and shut the door. Then I scurried to my feet in my staple sleepwear—a bra and thong—and fended off John, who was growling with his nose to the closet. Once I got him outside my room and closed the door, I sat down on my bed and thought I was going into cardiac arrest. I was gasping for breath as I tried to figure out what to do next. I was scared of both dogs at that point—I didn’t know what they were capable of after seeing Tammy basically shape-shift into an anaconda.

When I moved my hand to my chest to try to self-soothe, I realized my bra had been torn open and one of my breasts had been set loose and was bleeding. I looked over at Chunk, who at some point during the altercation had wrapped himself inside the drapes.

I don’t want to call Chunk a pussy, and I don’t want to call Tammy a cunt, but I want to just throw those two words out there.

I called Molly and told her that I was living with a real-life Cujo, and even though I knew it was Tammy’s fault, I was scared to open the door and check on John.

“I’ll come get him,” Molly said. It was 12:30 A.M., and while I waited for the coast to be clear, I texted Brandon to scan the security cameras in the morning and save whatever footage had just been captured for the next time me and my friends did mushrooms.

* * *

• • •

John never made the cut, because Tammy took him to task. Chunk knew better than to fight over territory he’d conquered long ago. He knew he belonged with me, but he understood there would be random dogs coming in and out of our lives, just the way people did.

* * *

• • •

Tammy was with me for three years and died shortly after the inauguration in January 2017. She felt the same way I did about Donald Trump. Molly and I were in South Africa at the time, and I got the call while Molly was out getting gifts for her brothers and sisters. She came back to the hotel room where I was sitting in a chair feeling guilty about traveling so much and not spending more time at home with Tammy.

“You gave her a good life, Chels,” Molly said, hugging me. “No one else would have ever adopted that dog. Do you know how much shorter her life would have been if you’d been home more? And, don’t forget, she brought me Hodor.*”

After Tammy died, I had some friends over for a small memorial service at my house, where we watched the video footage from my security cameras the night of the attack. It was the first time I had seen the crime scene, and Brandon had scored it to the theme song of Rocky. In it, you can see Tammy actually airborne after I got her off of John. The four teeth that I had campaigned for Tammy to keep ended up biting me in the tit. If I hadn’t busted my nut with my topless photo rampage years before, this video would have been released on all of my social media platforms, on a loop.

Watching the video of Tammy alone, pacing in my closet like a large brown bear, reminded me what a force of nature she was. She was an underdog and a badass. She was a fighter, and even though I don’t spend much time looking in the rearview mirror, my biggest regret is not ever getting her ears pierced.

* Which is what Molly renamed John. As it happens, John/Hodor wasn’t part Chow at all. Molly did his DNA testing and found out he is a purebred Leonberger. For the record, Tammy’s testing revealed she was a Keeshond/Shepherd mix with a tiny bit of Chow. So, my obsession with Chows comes from being misinformed time and time again that they are the breed I am rescuing, not from ever actually having one.

In our next session, Dan told me about self-defining relationships—the critical relationships that are formative, that determine the person you become. The relationships that, if they were to go away, would change you. You would never recover from the loss.

“So, everything goes back to Chet? Really?” I asked Dan. “That seems too obvious.”

“How do you mean?”

“Like, too easy. Is it really that simple? Am I really that simple?” Although it was a relief, at the same time it seemed like another cliché. Of course, that’s how simple this has always been.

“Well, it sounds twofold to me. It sounds like you had one injury when your brother died, which you’ve said you’ve never properly addressed, and the second trauma was the retreat of the rest of your family, your father especially. Let’s talk more about that.”

“I don’t remember much about those first few years after Chet died, other than that I had tons of problems at school. I became ‘trouble.’ ”

“Did you have ‘trouble’ at school before your brother died?” Dan asked me.

“I don’t really recall, but now that we’re talking about it, how much trouble could I have gotten into before the age of nine? It’s not like I was Satan. I think it was partly because my parents were so unreliable, so I think other parents wanted to avoid them, and partly because the attention I used to get at home had disappeared, and in response to that, I tried to get attention in other ways at school—however I could—which resulted in me constantly having to stay after school and sit in detention, and then, one by one, I was ostracized by all the friends I had in elementary school. Not because of my brother’s death, but because I had turned into someone else.”

Every once in a while I would self-analyze just to show Dan that I wasn’t a complete moron and also to surprise myself with what I’d known all along but had never said out loud.

My sister Simone and my brother Glen became my de facto parents after Chet died—or at least they were a more reasonable version of parents. I think Roy had gone off to live in Miami or something. He smoked a lot of pot, and needed a place he could do that without my father screaming at him all the time. Shana was there, but for some reason I don’t really remember her during that time.

But how much parenting could they have provided, really? Glen and Simone were both in college at Emory University, and anytime there was a crisis at home—of which there were many—one of them, usually Simone, had to manage it by phone from Atlanta. The crisis usually consisted of my father and me going to battle about the trouble I was in at school, my not listening to anything he or my mother told me, and my general lack of respect for anyone in a position of authority.

I became terrible. I hated everyone and everything. Shoving any pain in my pocket, hoping that eventually it would form a hole and fall out onto the street during one of my bike rides. I remember being on those bike rides, sailing past our neighbors’ houses so fast that the tears were blowing off my face. This is what the adults should be doing, I thought, figuring out a way to handle the situation without falling apart. I would force myself up the hills around our neighborhood on my banana-seat bicycle and think, You need to get stronger. Strength is what everyone in this family is missing—I’ll probably have to start lifting weights. I was dancing farther and farther away from myself.

I learned from Dan that being in motion was a way for me to avoid sitting still with my feelings. You can’t let anyone see you cry, so you

move.

Action is motion—is doing. Sitting is being. I had been a doer my entire life. I never sat still long enough to let anyone unglue my pain.

Dan wanted to know more about my father.

* * *

• • •

The best way to describe my father is that he’s a lot like Donald Trump, but less successful, thank God—otherwise, the damage he could have unleashed on innocent people could have been more widespread. I would use the word “shyster” to describe my father. He claimed his entire life that if his own father hadn’t died and left him a gas station, he’d be a civil rights attorney or a famous poet. “My father respected civil rights just about as much as he respected a hot pastrami sandwich,” I told Dan. Based on his confused facial expression, I put it in less abstract terms. “If one’s body is a temple, my father’s body is an IHOP. I don’t know much about his poetry, because—well, he’s not a famous poet, that’s why.”

I organized my thoughts and opinions of my father in the most succinct way I could, hoping to give Dan a clear overview without shocking him.

“He’s very nontraditional, and you’ll probably be alarmed by some of the things you hear—at least that’s my hope. Also, he wasn’t abusive. Verbally, at times, but not physically. He definitely spanked me a few times when I was little and smacked me across the face a couple of times when I was too old to be spanked, but that stopped when I finally hit him back one day. I would also like to add that I deserved to be hit.”

One can argue that no child deserves to be hit, but a slap across the face once or twice in your life sends a strong message, and the reason I don’t have children is partly because of my belief in sending a strong message to people when they are assholes, and lots of kids are assholes.

I went on to tell Dan about going with my father to Friday night services at temple, which used to be our thing when I was a little girl. My mom let me dress up in whatever ridiculous outfit I wanted, which was usually a combination of anything hot pink combined with red. I thought for a long time those two colors were great together, until later in life when I fashioned the phrase “summer whore” to describe that very look. My mom would slap some tights on me for good measure, and my father and I would go on our date night.

After Chet died, my dad didn’t want to go to temple, but my mother somehow convinced him that I needed to go, which was silly in the sense that I had no regard for religion. Temple was about me being my dad’s favorite. None of the older kids ever wanted to go to temple on a Friday night, because they had more interesting things to do.

If I could get him to temple, he would have to hold hands with me—that was our jam when I was a little girl. I’d get dressed up, and he’d show me off to the congregation, and then when the rabbi would ask one of the kids to answer whatever question he posed to the congregation, I’d raise my hand, and the rabbi would always call on me—probably because no other kids raised their hands. Then I’d run up to the bimah, and the rabbi would pick me up, and I’d whisper into his ear, “I don’t know,” really loudly. Then the whole congregation would laugh, and I’d run back to my father, and he’d put me in his lap, and we would both be beaming.

But, now that I was nine or ten, I wasn’t so little, so my outfits were no longer cute—I looked more like a child prostitute—and the only person who still was physically able to pick me up had gone off and let himself die. Temple was a disaster that night because everyone in the synagogue was coming up to my father and telling him how sorry they were about Chet. Fuck, I remember thinking. When were people going to get over this already? I was trying to get my father back to some sort of routine, and all these people kept interrupting my progress.

There were cookies after every Friday night service, so afterward, I excused myself to go collect them and bring some back home for my mother. When I came back to look for my dad, I couldn’t find him anywhere and I started to panic. I ran back and forth through all the rooms in the temple in search of him. Where was he? Did something happen? No, no, no.

My panic turned to hysteria. A woman I knew from temple saw me and came over to me and tried to calm me down. I hadn’t cried in front of anyone for months, so it was more like hyperventilating. Not being able to breathe, but not crying. Like the girl in Jaws, who saw her boyfriend get eaten by the shark and was left out to sea for hours until Roy Scheider found her inside the sailboat curled up in a ball, in shock.

More people were gathering around, and then a woman kneeled down in front of me, put her hands on my shoulders, and told me to breathe. Then someone in the crowd whispered to someone else that he had seen my father leave moments earlier and that he seemed out of it. He had driven home without me.

I wanted to die right then and there. I remember telling the people standing around me that I was fine to walk home. I don’t even know if I knew how to get home from temple at that age. Plus, it would have been nine P.M. on a Friday night. Maybe I’d get hit by a car and then my father would have no choice but to wake up. Two dead kids. That would teach him.

The rabbi came over, and I remember seeing him in plain clothes without his Jewish garb on and wondering if he was going to take me home with him and if I would just become part of his family. He wouldn’t forget to pick me up, and his clothes were clean and pressed, and he seemed so normal—like a professional. Professionals showed up when they were supposed to. Why couldn’t my dad just be more professional?

Instead, the rabbi drove me home, and when we got to our house, my dad’s car was in the driveway, and our rabbi walked me to the front door. “Your dad is in a lot of pain, Chelsea,” he said. “I know you must be too.”

“I just have a stomachache,” I told him. “I’m fine.”

“If it’s okay with you, I’m going to come inside and talk to him.”

“Okay,” I said.

I opened the front door, which was always left unlocked, and all the lights were off. Of course. Everyone was asleep.

I needed to recover these optics quickly. “He’s just sick,” I told the rabbi as we stood in the darkness of our front hallway. “He’s got a heart condition, and sometimes he gets heart attacks.”

My rabbi kissed me on the forehead and said something in Hebrew that I didn’t understand.

* * *

• • •

Dan told me to stop talking. To sit with the feeling of my father driving home without me. Sitting with my feelings meant it was time to cry again.

I wondered how many more sessions would be like this. It was fucking exhausting, and our sessions were in the morning, which meant I’d show up to work for hair and makeup looking like I had just gotten into a fight with a cherry snow cone.

I put myself through this because it was a psychological workout. It was easy to not address my own issues and to focus on everyone else’s. Judging other people had become my way of avoiding judgment of myself, and I had to do better than that. Going back to Dan week after week, knowing that I was stripping away all the layers of protection I had spent years fortifying, was particularly dreadful. I knew it was worth continuing. If you went to the gym every day, you were going to get stronger; this was my mental gym.

“Also,” I added, when I felt like enough time had passed, “my parents did this kind of shit all the time. They’d forget to pick us up from Hebrew school, or regular school, and it wasn’t just me. It happened to my brothers and sisters before I was born, so I don’t think we can blame this on Chet. My sister Simone went to school with the three older boys for an entire week when she was four years old, because my mom thought you could just do that. She didn’t really understand how things worked in this country.”

“What do you mean? Where was she from?”

“She was German, but she was fluent in English. That wasn’t the problem. She was just so laissez-faire about everything. The school called her and told her that Simone wasn’t old enough

for kindergarten and they couldn’t allow her to keep coming. You have to understand that my parents were not equipped for or interested in conventional parenting. They were off, and they were like that before Chet died. My dad worked when the older kids were growing up, and I guess my mother was usually asleep, so it was always mayhem. It probably was worse for me because the older kids were all gone, and that was after my dad had sold the gas station and worked from home, which meant he had a big oak desk with a lot of papers on it that meant nothing, and a big room he called his ‘office.’ Oh, and he had a fax machine. He never shut the fuck up about that either. He’d tell waiters at restaurants that they could fax him the bill—as if that were ever an option in any sort of reality, ever. He also used a toothbrush to comb my hair when I couldn’t find a hairbrush one morning before school and my mom was away somewhere. I just want you to know the kind of operation my parents were running.”

“Was your mother depressed?”

“Maybe, but she also just loved to sleep. My grandmother—who was a Nazi, by the way—would always tell the story that the teacher at my mother’s school in Germany used to find her taking naps underneath the staircase every afternoon. She just loved sleeping. Our whole family can sleep for hours, especially when we’re all together. Either we bore the shit out of one another or it’s genetic. I can sleep for fourteen hours straight. With a Xanax, twenty.”

“We can talk about the Xanax later. Was your grandmother really a Nazi?”

“No, not really, but she was in Germany during the war, so she was complicit. Like Ivanka.”

“Okay, back to your father.”

“Right. After that, my father and I couldn’t be in the same room for a long period of time without screaming at each other. All I wanted to do was get out of the house and stay out of the house, and all my father seemed to want to do was force me to sit at home and punish me.”

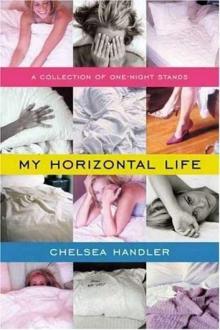

My Horizontal Life: A Collection of One-Night Stands

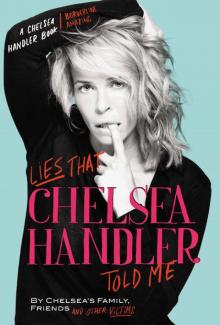

My Horizontal Life: A Collection of One-Night Stands Lies That Chelsea Handler Told Me

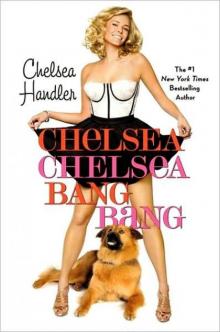

Lies That Chelsea Handler Told Me Chelsea Chelsea Bang Bang

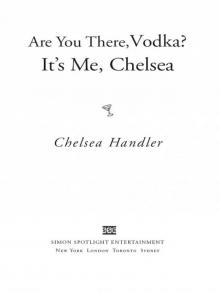

Chelsea Chelsea Bang Bang Are You There, Vodka? It's Me, Chelsea

Are You There, Vodka? It's Me, Chelsea Uganda Be Kidding Me

Uganda Be Kidding Me Life Will Be the Death of Me

Life Will Be the Death of Me