- Home

- Chelsea Handler

Life Will Be the Death of Me Page 3

Life Will Be the Death of Me Read online

Page 3

“I’m a big proponent of being responsible for your own happiness,” I continued, “and have always had a surfeit of dopamine to go along with it, so the only thing I really want to work on is my temper and impulse control…or, at the very least, behavior modification. I’m basically looking for a behaviorist. Like, for a puppy. I’d like to learn how to make my point without yelling.”

Our first few sessions consisted of Dan guiding me through meditation, after which I would spend the rest of the time bitching about Donald Trump and what a piece of shit he was. I was paying someone hundreds of dollars an hour to complain about Donald Trump, which seemed like the exact right move. I would have paid him double. I had definitely paid for far worse in my life. I knew people were getting sick and tired of my anger directed toward the 2016 election and the daily horrifying cabinet appointees, and Ivanka and that schmuck Jared, and that evil witch they called a press secretary. I couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that Sarah Suckabee Sanders and Ivanka Trump had no morality or sense of obligation to the very sex they inhabited—to stand up and say, No more. I needed someone to let me vent, privately. I needed someone to help me harness my anger into something positive.

In our third session, Dan asked me about my childhood.

“Just the usual bullshit: my parents were kind of lame, I have five brothers and sisters, one of whom died when he was twenty-two, and my mom died a few years ago—I don’t really have any sense of time, so it could have been ten years ago…or five years, I really don’t know, but I’d rather talk about right now. What can I do right now?”

He looked at me with something in his eyes that I had seen before from doctors when I mentioned that my brother had died, and that slightly annoyed me because I was paying him to talk about what I wanted to talk about, which was the present—not the past. It felt like pity, and that wasn’t something I was interested in being on the receiving end of.

Of course I wanted to talk about my brother, but I wasn’t about to admit that to a stranger.

Now, I know that I was testing him. He was earning my trust. I had to make sure I respected him, and I had to make sure he wasn’t going to let me steamroll him. All I knew at the time was that I felt a responsibility, to myself and to my friends and to all the other people I loved, to keep going to my appointments with him. I didn’t always feel like going—the same way I felt about meditating—but I felt that it was my duty to start doing more things that I didn’t feel like doing. Something was pulling me toward him—it was as if my biological clock were telling me that I needed a psychiatrist before I wouldn’t be able to reproduce anymore.

It was during our fifth or sixth session that he asked me if I had ever heard of something called the Enneagram. I hadn’t. I asked him if it was a heart monitor. It’s not.

The Enneagram is a psychological system based on certain ancient approaches to viewing our lives. More recently, the philosophy was adapted and popularized in the United States by a number of people as a personality test and tool for self-discovery. Dan, my therapist, and other physicians and researchers have been using variations of the Enneagram to explore the idea that there is a scientifically recognized brain-based personality pattern that develops and manifests over the course of our lives. Dan applies something called a PDP model, which stands for patterns of developmental pathways. Basically, this method suggests that most people are born with a tendency toward one of three default zones based on how you contend with the separation that occurs when you leave the womb, where you are safe and warm and nourished for nine months, and are then catapulted into a hospital room with harsh fluorescent lights shining on you (if you’re lucky), where you are greeted with a smack on the ass and you have to cry every time you want to eat or are in pain, because suddenly that’s the only way to communicate your needs. Or something like that. Anyway, Dan says how you navigate this transition from the inner peace of the womb to the struggles of the world outside of it is an important factor in determining your personality.

I gave him a skeptical look. When he asked me what I was thinking, I told him that this sounded very LA.

“What do you mean?” he asked earnestly.

“You know…I mean, are people really holding on to their births all these years later? I just find that a little hard to believe. Now people are going to be pissed about being born? It’s a little much, no?”

He cocked his head to the side, and I didn’t know if it was meant to challenge me, or if he was sincerely confused by my Los Angeles reference.

“I just have a hard time comprehending why rehashing the past repeatedly, time and time again, is beneficial to people who just need to get up and move the fuck on. Get over it. There are people being blown out of their homes in Syria. We have a president who is rolling back women’s rights, and innocent black men are getting shot and killed by police officers every day. Get out of your own asshole, and look around.”

The irony that I was sitting in a psychiatrist’s office complaining about people who sit in a psychiatrist’s office was not lost on either of us. We locked eyes with an intense stare because what I had admitted was more profound than anything I was blabbering on about; I had sought out the help of a professional because I knew, on a cellular level, that I wouldn’t be able to help anyone in a real, meaningful way until I was able to sit with myself—a place I believed I was too smart to ever have to go to.

“Okay, that’s fair,” he said, nodding, understanding where I was coming from. “Just so you know, from my professional experience, I have seen how it has helped a lot of people to understand themselves and the people they love in a deeper way. But we don’t have to talk about it. It’s totally up to you.”

I told him what my father told me about taking one piece of information away from any conversation and that one of my desires was to become more open-minded, as long as I was learning something, and if this was something he believed in, I was willing to hear him out.

“Your father sounds like a smart guy,” Dan said.

“Well, let’s not get carried away. I mean, he was and is smart, but he’s also a con man who cheated, lied, and probably stole from people. He is the epitome of a used-car dealer.”

“In what way?”

“He actually was a used-car dealer.”

“Ah, okay.”

“But please go on, because I’m here to become less judgmental, and more patient, and if I really lose interest in this subject matter, I’ll start rolling my eyes, which is also something I’d like to do less frequently.”

He went on to tell me that this default zone is the place you revert to when you feel uncomfortable, or nervous, or when things don’t turn out the way they were supposed to. When you are born into this world, you experience one of the three reactions, which sets up your disposition in life. In the Enneagram model, the reactions are located in the head, heart, and gut. Dan and his fellow researchers developed their own model, translating those three areas of the body to emotional states: fear (head), sadness (heart), and anger (gut).

“I’m anger.”

“Okay.”

“I’m fucking angry. I just don’t understand how this man could get elected.”

Dan told me to just sit with that feeling and not talk.

What I grew to learn was that Dan didn’t want me to talk around my anger and pretend it was all about Donald Trump. What Donald Trump represented to me were things being out of control, and when things became unhinged, I became angry because that was my default zone. I realize that many people may think of me as someone who is completely out of control myself, and they’re not wrong. I am out of control, but within boundaries that no one knows about except me. I thrive in organized chaos. It keeps my juices flowing and it keeps me paying attention and on my tippy-toes.

Once the silence had gone on for what seemed to me like an unreasonable amount of time (less than a minute), I

needed to break it.

“Anger makes sense,” I admitted. “All I ever wanted was financial freedom and independence and now I have it, but I’m stuck. I’m stuck with what to do next, because the whole world is upside down. Until I read Rebecca Solnit and James Baldwin and Ta-Nehisi Coates I had no idea how many women are beaten and raped every second in this world or what it means to grow up as a black person, or any person of color, in this country we call ‘the land of the free and the home of the brave.’ What is wrong with me? How could I be so self-absorbed?”

I was saying things out loud I hadn’t said out loud to anyone before.

“I’ve spent the last fifteen years of my success believing that I picked myself up by my bootstraps and worked my ass off to get where I was. It never occurred to me that I have had an advantage just by being white. That I’ve never not argued with a police officer when being pulled over for a ticket, while for black people getting pulled over is a life-or-death situation. I’ve been so consumed with my own success and my own personal life that I haven’t spent enough time thinking about people outside my lane and what their struggles are. I have shame for my entitlement and for not learning all of this sooner. I feel great shame and outrage. I’m embarrassed for our entire race, but I’m really mostly embarrassed for myself.”

By the time I was done with this little diatribe, my eyes were starting to water. I needed to pivot and change topics before the lip-quivering kicked in. It would be mortifying to lose my composure in front of a stranger. I was not going to let myself cry.

“I come on strong.”

“To whom?”

“To anyone who I think needs me.”

“Tell me more about that.”

“I want to fix people. If someone doesn’t have friends, I’ll introduce them to people. If someone needs money, I’ll give them money. If someone is hurt and is going through a breakup in Germany, I will fly to Germany to be with them. They don’t really even have to be a close friend. I’d do that for a stranger. I have a boundary issue, I think. Why do I do these things unless I am making up for some other terrible quality that I’m trying to camouflage? It’s too much. I always go too far. I’m like a calf that needs to be faked out with an electric fence inside a bigger electric fence, like a Russian nesting doll. I have to be tricked to stay inbounds. Like an animal. I hate boundaries.”

Dan looked at me with concern, but it was concern that I needed. I needed someone who didn’t know me to be concerned for me, and it seemed like a more straightforward transaction to pay someone to do it.

“Okay, so, back to the Enneagram,” I said. “So, how you enter this world determines your natural disposition for the rest of your life? Is this astrology-adjacent?”

“I don’t view it as that, no. But if you are hesitant about diving in further, then we don’t have to discuss it at all.”

“You have a medical degree, right?”

“I do.” He nodded, smiling. “I’ve also trained as a researcher, so a lot of the research I’ve done on the Enneagram with other scientists and other researchers is something I’m very familiar with. If I didn’t think it held any merit, I wouldn’t be writing about it or talking about it.”

Okay, calm down, big guy is what I wanted to say, but I felt at that point he had gotten a full dose of my cynicism, and the truth was that I did want to hear more.

“Obviously, there are other factors, such as nature and nurture, along with all of the events that happen throughout your early childhood and throughout your life that will shape who you become as a person,” he said. “But that anger, sadness, or fear will remain deep in your subconscious, and will dictate how you react to things in your life that don’t go as planned.”

Dan asked me about my parents’ marriage, and I told him it was functionally dysfunctional. That my parents were hard to take seriously as role models, but that my aversion to being married wasn’t about my parents’ marriage. It was about marriage in general; it seemed outdated.

“I consider remaining unmarried a victory,” I told him. “If I had married either of the men I’d thought about marrying, I would be divorced…therefore ending up as just another statistic. Conversely, remaining married to the same person your entire life seems not only boring, but also like becoming just another statistic. It feels like marriage goes hand in hand with, well…running errands, or baking.”

“You don’t run errands?” he asked, slightly confused.

“I try not to.”

I worked hard to maintain eye contact with him when I took breaks from rambling so that he would understand I was serious, even if some of the things I said sounded ridiculous. I was serious about getting help for my ridiculousness.

“Sorry, I know you’re married, and it’s not an insult,” I told him. “I just prefer to not do what everyone else is doing. I like to be in the minority.”

“No offense taken,” he assured me, smiling slightly.

“I think I’m more cut out for short flings, or long-distance relationships, casual encounters. I don’t think I have what it takes to remain interested in someone long term. The word ‘marriage’ has always felt to me like the end of fun.”

“Okay,” he said, leaning his head to one side.

“I don’t like constraints or restrictions of any kind. I don’t like feeling boxed in. A one-on-one beach holiday with someone of the opposite sex is something I’d like to avoid at all costs. I’d rather be alone.”

At this point in my life, I didn’t know if anything I was saying was true or if I had manufactured all these thoughts to protect myself—I’m assuming it’s the latter, but the truth of the matter is when it comes to men, I haven’t been that impressed with my choices.

He asked me why I thought marriage represented the end of fun.

“I get bored easily, and I also go at things in a wildly immature way.”

“How so?”

“Like a little girl. Everything has to be the most, or the best, or dangerous, or a risk. I take everything too far. I don’t know how to just be still, unless I’m lying in bed binge-watching Peaky Blinders or if I’m at a long, leisurely lunch, anywhere pleasant in this world. Then I can sit for hours, but that scenario involves Aperol spritzes and other people who feel as passionately as I do about Aperol spritzes. This is why I can’t meditate.”

“Because of Aperol spritzes?”

“Because I like extremes. I think I’m an extremist.”

“Tell me about that.”

“It’s the ‘everything is a possibility’ phase that I live for. I don’t ever want another person making the decisions about where I go or what I do, or to be sent down a particular runway I haven’t approved. I want to change runways all the time, and I don’t like answering to others. I don’t like feeling trapped, or having to get approval to go on a trip from anyone. I want to do what I want to do when I want to do it. I’m completely fucking spoiled.”

“Okay, talk more about that,” he said.

“I feel like I’m always running a million miles an hour, and that I’ve covered a lot of ground, and I like that my life is so full. I’ve had so many adventures, but there are never enough. There’s too much to see, too many books I haven’t read, and too many people that need help. I do feel grateful. When I stop being grateful for something, I usually end it. I stopped doing stand-up because I burned myself out. I did too many shows and too much traveling and wrote too many books in a row to be grateful. It became rote. I was becoming devoid of the joy one should have when walking out to a crowd of thousands of people. I grew impatient and irritable, and I felt icky having those thoughts in front of people who had paid money to come see me, all the while dying for it to be over so I could just hang out with whoever was on the road with me. I didn’t enjoy being on the stage as much as I enjoyed walking off it. I liked the sense of accomplishment—and all the great luxurio

us things that came with it—but once I realized my heart wasn’t in it, I felt like I was ripping people off, and I was done.”

“What does it feel like to you when you are not running around making yourself busy?” he asked me, leaning forward in his chair, putting both hands on his knees.

“I have no idea, because I’ve never done that. This is what I do with everything. I burn the candle at both ends, and then I grow bored.”

“Do you think that you’re running from something?”

“I don’t know, because that’s how I’ve always gone through life,” I told him. “I get sick of people, places, jobs, things. I’m always looking for newness. Something fresh, someone new, a stranger, the unknown.”

I told him that when I was a kid I was so hungry to grow up and become famous and successful that my entire twenties and half of my thirties were spent in a cycle of feeding that hunger and then looking for something else. I had now reached the burnout phase with my talk show. I was sick of all the things that went along with doing a talk show. The editing, the talent booking, the constant micromanaging, and having to watch myself on camera over and over again.

I was over it.

Dan asked me about children, and I repeated what I tell everyone who asks. “I’ve never had the urge. It wouldn’t be a good use of my time.”

I asked him to tell me more about fear and sadness. I wanted to make sure I could rule those two things out.

He told me that people whose default is fear tend to second-guess everything they do. They tend to be indecisive, and many end up leading very safe lives. They are not interested in risk or adventure—they are interested in sameness and security. They are people who typically do not switch careers midlife or go skydiving or take great risks. They are also conflict-averse.

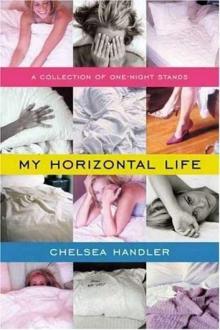

My Horizontal Life: A Collection of One-Night Stands

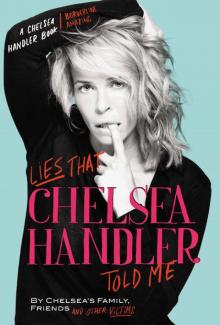

My Horizontal Life: A Collection of One-Night Stands Lies That Chelsea Handler Told Me

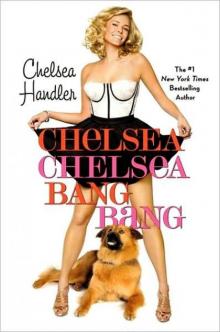

Lies That Chelsea Handler Told Me Chelsea Chelsea Bang Bang

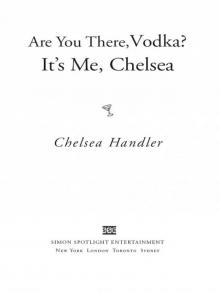

Chelsea Chelsea Bang Bang Are You There, Vodka? It's Me, Chelsea

Are You There, Vodka? It's Me, Chelsea Uganda Be Kidding Me

Uganda Be Kidding Me Life Will Be the Death of Me

Life Will Be the Death of Me